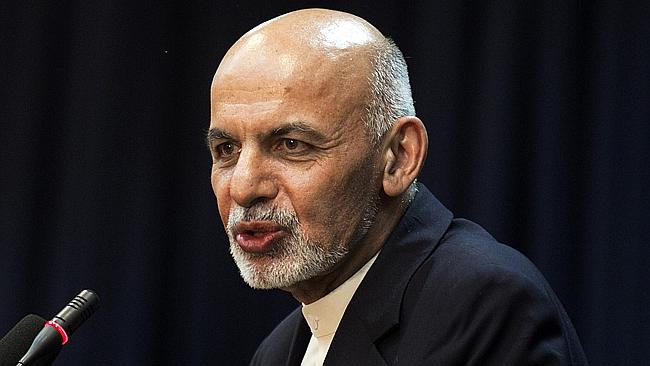

Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani has taken a tough and somewhat unexpectedly blunt stance on the tens of thousands of his citizens who are fleeing the country to make the dangerous journey to Europe.

“I have no sympathy,” the Afghan leader told me in his palace in Kabul. He is calling on his countrymen to return to the war-ravaged nation in an effort to rebuild it.

But do his words carry the weight they should, in a country that is increasingly feeling frustrated with the political elite, and a sense of hopelessness about their future?

Convincing people to stay feels like an impossible task for what is perhaps one of the toughest jobs in the world, being Afghanistan’s president. Ashraf Ghani was sworn in in September 2014 after controversial elections. This led to the formation of a national unity government with his main rival, Abdullah Abdullah, appointed as chief executive officer. Since then, Mr Ghani has had to deal with a shrinking economy, high unemployment, a perilous security situation thanks to a resurgent Taliban and an ineffective government, further weakened by his troubled partnership with Dr Abdullah.

‘Defiant’

It is no wonder, then, that Afghans make up the second largest group, after Syrians, to flee to Europe. In the past year alone, 180,000 nationals have fled instability and economic hardship at home.

But who should take responsibility for the tens of thousands of Afghans who have turned up on European shores? In a wide-ranging interview, Ashraf Ghani demanded that these migrants return home. “We have spent hundreds of millions of dollars [on people] who want to leave under the slightest pressure. You need to have the will if you want to have a country.” The president may be taking a defiant position, but many Afghans at home and abroad feel resentment towards Mr Ghani for not calling on his own children, who live in the United States, to return. While he has inherited some of the problems he faces today, his approval rating continues to plummet with many Afghans feeling he has failed to manage expectations. And these latest statements are likely to cause a further drop.

It is not yet two years since he came to power and already in Kabul there is a sense of nostalgia for the past, with many referring to the era of his predecessor Hamid Karzai as the “good days”.

The president is very much aware of the situation on the ground and believes Afghans should confront it. Last year, more than 11,000 civilians were killed or wounded in the country. One in four were children. That’s the highest number recorded since the US-led invasion 14 years ago. The United Nations says if Afghanistan’s national unity government survives 2016, it will consider it a success. The bar is pretty low. And the Afghan people feel increasingly frustrated. A recent BBG-Gallup survey indicated that nearly 69% of people say their lives have got worse in the past year. 81% of people are dissatisfied with the government and 76% with Ashraf Ghani.

It appears that no matter what assurances the president gives people about how he intends to boost the economy and create jobs, the fact remains that this is a nation that continues to be heavily dependent on the international community for both security and economic assistance.

The deteriorating conditions also highlight the international community’s failure to deal with the insecurity in Afghanistan. Nato and its partner nations have roughly 12,000 troops stationed there, yet the Taliban’s reach is wider than at any time since 2001. ‘Talking fiction’

When President Ghani was sworn in, he immediately oversaw the signing of a controversial pact with the US known as the bilateral security agreement. It’s controversial because Hamid Karzai had incensed the Obama Administration by refusing to agree to the deal until his demands had been met, souring relations between Washington and Kabul.

This was something Ghani had vowed to mend. With Nato troops remaining in the country, it was supposed to protect Afghan interests and make Afghanistan safer. The security situation now is the worst it’s been since 2001.

The insurgents have been invited to the negotiating table many times but say they won’t be coming while foreign troops remain in the country. And why would the Taliban bother striking a peace deal with the government when they have made such significant gains in the battlefield?

When I asked the Afghan president about growing concerns that the southern province of Helmand could collapse to the Taliban, he dismissed them. “Every place they’ve made gains, we’ve reversed them. Concerns are one thing, I’m talking fact, you’re talking fiction.” But according to the independent Afghan Analysts Network, the Taliban are now better organised, better equipped and have developed sanctuaries in Afghanistan. In a report released this month, the AAN has given a detailed breakdown of the districts the Taliban are currently in control of in Helmand province.

There is no doubt that the Afghan president is in a tough position. He and his fragile unity government face the difficult balancing act of stabilising the security situation and providing assurances to the Afghan people that their future prospects are not entirely doomed.

But with 60% of the population under the age of 20, it is clearly proving hard for the Afghan leader to convince them that there is hope for a better future if they remain in the country.

The central government also fears that it is mostly the educated middle class who are leaving. This means it will be an even greater struggle to rebuild Afghanistan after years of conflict. (BBC)

Afghanistan Times

Afghanistan Times