By Satish Chandra-Men coming from Afghanistan move down a corridor between security fences at the border post in Torkham, Pakistan on the Durand Line on 18 June 2016. REUTERS

All successive Afghan regimes since 1947 have refrained from granting de jure recognition to the Durand Line.

In a welcome departure from the past, we are beginning to see the evolution of a new get tough policy by the government vis-à-vis Pakistan, designed to impose costs on it for the continued export of terror to India. Some initial indicators of this are the abandonment of the dialogue process, the diplomatic campaign to isolate Pakistan as the fount of terror, highlighting its human rights violations in Gilgit-Baltistan, PoK, Balochistan, Pakhtunistan, and Sindh and the resulting discontent there, the surgical strikes, the effort to maximise the utilisation of the Indus waters, etc. Not only will these moves have to be sustained, but much more will need to be done over the years in order to make Pakistan desist from its use of terror as an instrument of foreign policy against India. An innovative, low cost, and effective step, which can be taken by India towards this end, is to weigh in, at an appropriate occasion, against the legitimacy of the Durand Line.

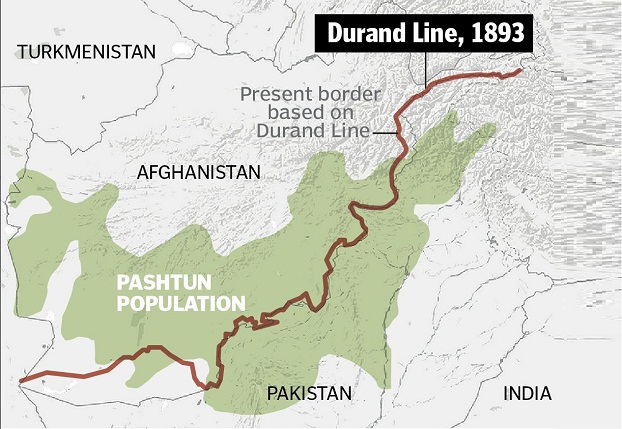

Established in 1893, through an agreement between the Indian Government and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan of Afghanistan, the Durand Line was designed to demarcate the “respective spheres of influence” of British India and Afghanistan. It is a matter of record that it has, since inception, been mired in controversy.

The Durand Line was never intended to constitute an international border between Afghanistan and India, but merely to mark the limits of the spheres of influence of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan and British India. Indeed, after signing the Agreement, Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, the Indian Foreign Secretary, had no hesitation in asserting that “The tribes on the Indian side are not to be considered as within British territory. They are simply under our influence in the technical sense of the term…” That the Durand Line merely marked spheres of influence, and not territorial limits, is further borne out by the fact that the British right till 1947 allowed the tribals under their sphere of influence to conduct their own affairs without any hindrance and did not attempt to bring them under their administration, much less occupy the area.

Pakistan has consistently failed to observe the assurance of non interference “in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of Afghanistan”, which was expressly provided for in the 1893 Durand Line Agreement.

It may also be underlined that the Durand Line took no cognisance of the ethnic groups in the region and divided not only the Pashtuns, but also the Mohmands and Waziris. Since the separation effected by the line was not territorial in nature, tribes on both sides of it freely interacted with each other and conducted trade on both sides of the line.

Above all, contrary to what is made out by Pakistan, the Durand Line established by the agreement of 1893 did not put in place a clearly defined and sacrosanct international border.

Afghanistan has, over the years, repeatedly questioned the alignment of the line as projected by the British, with Amir Abdur Rahman Khan at the very outset asserting in 1895 that he was to receive the entire Mohmand territory and not just a part of it. It is also significant that the line defied delimitation and demarcation for decades due to differences of interpretation.

After the 1893 agreement, the alignment of the Durand Line saw repeated changes emanating from the agreements of 1905, 1919 and 1921. The agreements of 1893 and 1905 were in the nature of personal agreements between successive Amirs of Afghanistan and the British government, and those of 1919 and 1921 were between the governments of the two countries. Significantly, the treaty of 1919 was concluded in cancellation of all previous treaties. Furthermore, the treaty of 1921 expressly provided in Article 14 that either side could denounce it with one year’s notice.

Given Afghanistan’s long standing and deep rooted unhappiness with the Durand Line, it is no surprise that in 1949, soon after the departure of the British from the Indian subcontinent, it repudiated all treaties made with the latter. Indeed, it was on this issue that in 1948 it opposed Pakistan’s joining the UN. All successive Afghan regimes since 1947, whether monarchist, republican, communist, Islamist, or democratic, have refrained from granting de jure recognition to the Durand Line. Even the Pakistan sponsored and supported Taliban regime had no compunction in resisting Pakistani pressures to accept the Durand Line.

It is ironic that while Pakistan swears by the sanctity of the Durand Line it has consistently failed to observe the assurance of non interference “in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of Afghanistan”, which was expressly provided for in the 1893 Durand Line Agreement. In a similar vein, the 1921 agreement unequivocally guaranteed to Afghanistan “all rights of internal and external independence”, which too have been consistently ignored by Pakistan.

Regrettably, both the US and the UK have made known their acceptance of the Durand Line. This is the result, no doubt, of their historic tilt towards Pakistan, as the legitimacy of the line is clearly questionable.

Indeed, a British House of Commons 20 June 2010 research paper found that “The legal status of the Durand Line has never been definitively settled. Although the British policy was and remains that the line represents a legal frontier, Afghan arguments that it was never intended as such have considerable credibility…”

Given the dubious legitimacy of the Durand Line as a legal frontier between Afghanistan and Pakistan and the latter’s implacable hostility towards India, it is worth considering the possibility of expressing our reservations about it at an appropriate occasion. This is all the more so as independent India has so far refrained from taking any firm official position on the Durand Line. The reported off the cuff remark to the media on return from Iran by Atal Behari Vajpayee, as External Affairs Minister, way back in May 1978, that the Durand Line be respected by Afghanistan and differences be settled through negotiations, was a one-off comment and cannot be regarded as binding on India today, particularly in the light of Pakistan’s increasingly hostile moves towards it in recent times.

A clear-cut stance by India against the Durand Line as a legal frontier between Afghanistan and Pakistan would redound to its benefit in two ways. Firstly, it would take the already excellent India-Afghanistan relations to an even higher level, as no other country has supported it on this issue. Indeed, even the Taliban would find it difficult not to be appreciative of India for this step. Secondly, it would promote the unravelling of Pakistan, which India needs to seriously consider as the ultimate riposte to the former’s relentless use of terror against it.

The downside of coming out against the Durand Line is negligible. Pakistan will, no doubt, be upset, but that is nothing new. There will also be those who may argue that we cannot object to the Durand Line while calling for the acceptance of the McMahon Line.

This line of argumentation is flawed, as the latter clearly marked territoriality, while the former merely marked spheres of influence and cannot be regarded as constituting a formal boundary between two sovereign nations. Moreover, non interference in Afghanistan, a critical component of the Durand Line agreement, was not observed by Pakistan and the line was, furthermore, formally rejected by Afghanistan as per the provisions of the 1921 agreement.

Satish Chandra was formerly High Commissioner to Pakistan and later Deputy National Security Advisor.

Afghanistan Times

Afghanistan Times