By Safiullah Taye and Alias Wardak

On March 24, the U.S. State Department announced to cut US$ 1billion of its aid to Afghanistan this year, with a possible further reduction of US$ 1billion in 2021. While acknowledging the financial impact of the State Department’s decision, this analysis is considering the political ramifications of the reduction in aid to be greater on the Afghan government. By virtue of being the recognized President of the Republic, it is only fair to examine the perplexities of today’s conundrum in Kabul through the Arg’s perspective and what options are ahead of President Ghani.

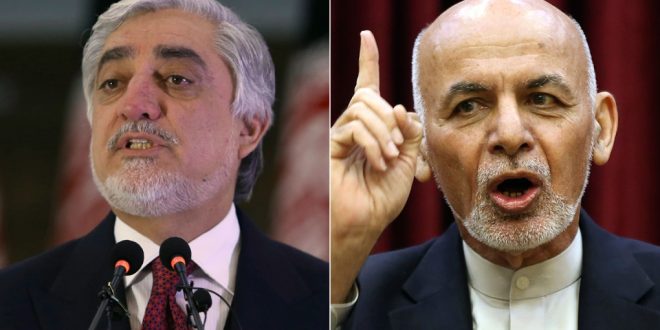

Afghanistan is at one of its most crucial and fragile junctions since 2001. While the Republic is in a distressed need of being saved, President Ghani is loggerheaded with challenging issues of losing financial assistance from Afghanistan’s most supportive donor, battling with Dr. Abdullah, negotiating with the Taliban, and all of these in the midst of a global pandemic.

In a live address to the nation, President Ghani declared that the U.S. aid reduction stands to have no impact on Afghanistan and its key sectors. According to TOLONews, he later directed the Deputy Ministers of Defence, Interior, and Finance to save US$ 1billoin in the security and defense sector. Yet undoubtedly, any sudden reduction in foreign aid would cause fiscal shocks to the aid-dependent economy and undermine the capacity of the government to maintain basic services. A report by the Biruni Institute in Kabul has recently projected an 11 percent fall in the economic growth rate of the country. The same report also suggests that with the spread of the COVID19, a reduction in government expenditure can have devastating impacts on the lives and livelihoods of millions of Afghans.

To further contextualize Afghanistan’s aid dependency, on average, 65 percent of all government expenditure in Afghanistan has been provided by foreign aid since 2002. Additionally, over 90 percent of Afghanistan’s military budget is funded by donors, with the country relying on various grants for supporting its security and economic development sectors. During a 2018 interview with CBS 60 Minutes, President Ghani even acknowledged his government’s almost absolute dependence on Washington, stating that “we will not be able to support our army for six months without U.S. support, and U.S. capabilities.” Hence, there is no doubt that the reduction of aid in the midst of a global pandemic, and a further reduction of US$ 1billion in 2021 will further cripple the country’s economy. That is all being said, the reduction in aid is, indeed, due to the current political deadlock in Kabul.

The reduction in aid has a deeper political ramification for President Ghani. The cut in the U.S. aid is affecting President Ghani’s reputation of having an “excellent relationship” with President Trump. But, Washington’s support also comes with certain expectations. After the U.S.-Taliban deal, President Ghani raised concerns over the release of 5,000 Taliban prisoners, a key element in the agreement. Despite what perhaps the U.S. was expecting, President Ghani soon began to show his inconsistencies by delaying the release of the Taliban prisoners and struggling to put forward an inclusive negotiating team with the Taliban. Moreover, what seems to frustrate Washington is the political deadlock between Ghani and Abdullah, stating that the U.S. is “disappointed in them and what their conduct means for Afghanistan and our shared interests.”

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s unannounced visit to Kabul on March 23 was meant to show the commitment of the U.S. to all three overdue issues of, releasing the Taliban prisoners, selecting the negotiating team, and forming an inclusive government. The cut in aid, as a response to the deadlock between President Ghani and Abdullah, hence show the fragility of the U.S.-Ghani relationship.

For the U.S. while it is important to continue supporting Afghanistan, there is also an urgent task of cementing its peace agreement with the Taliban. But in order to achieve that, there has to be some political stabilities in Kabul to ensure that the terms of the deal are respected by Kabul, and that the Afghans are able to effectively engage in negotiations with the Taliban. Moreover, while there is no guarantee that the Taliban will hold their end of the deal, the U.S. wants to ensure some degrees of compromise and consistency with President Ghani.

And that takes President Ghani to his second issue, the domestic fragmentation, and power struggle. We believe that there has been enough media coverage and newspaper articles on the political deadlock between Dr. Ashraf Ghani and Dr. Abdullah. There is certainly no doubt that the saga has had devastating impacts on Afghanistan’s economy, and politics if not other areas. Even the U.S. State Department statement stresses that leadership failure in Afghanistan “has harmed U.S.-Afghanistan relations and, sadly, dishonors those Afghans, American, and Coalition partners who have sacrificed their lives and treasure in the struggle to build a new future for this country.” Hence, though the cut is a direct product of the political deadlock in Kabul, the U.S. is certainly more concerned about the impact of these issues on its agreement with the Taliban.

And thirdly, President Ghani’s tale with the Taliban. Although President Ghani has been more “politically correct” with the Taliban, certain members of his inner circle have been vocal in their opposition to the Taliban. But the consistent message from the Arg has been, no sidelining of the government and that any negotiations with the Taliban must be through the government channels. In addition to that, there has been the protracted issue of finalizing the list of negotiating team with the Taliban. Although the list is finalized, and even Dr. Abdullah has endorsed the team, the Taliban have refused to meet with the team, arguing that it is not agreed upon by all effective Afghan sides and does not represent all sides. It would be difficult to fathom the accusation that the government has been jeopardizing the peace process, but indeed certain precarious and inconsistent policies of Arg has limited the Afghan government’s ability to maneuver in this dynamic political setting.

For most members of the international community, and most undoubtedly many Afghans, including millions of women and youth, the blaze of establishing the Islamic Emirates by several members of the Taliban is unsettling. While the leadership in Afghanistan has the chance, their effort must be on saving the Republic. In contemporary international relations, hegemons are supporting all types of government and should be an indicator for the Afghan leadership that no one is indispensable.

In this complex political puzzle, the next step for the Afghan government is crucial. First and foremost, any further gamble with the U.S. could cost the administration in Kabul and Afghanistan much more than US$ 1billion dollars. Even more importantly, any further domestic tensions could cost the government and the Afghan people their Republic. Thus, any compromise between the Afghan leadership at this point will be their greatest gift to the Republic. However, certainly, the Afghan leadership should be prepared for tough negotiations with the Taliban. The Islamic Republic must negotiate with the Taliban in their religious lexicon. While the selection of those at the negotiation table can be based on ethnic, social, political considerations, the government must have several working groups of experts in various areas of governance, including jurisprudence, prepared to support the negotiating team. Lastly, if there is any chance of reaching a deal with the Taliban, the Afghan leadership will lose the most if they are fractured from within.

Safi Taye is a Ph.D. candidate at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia. His dissertation focuses on Foreign Aid Negotiations in Afghanistan. He can be followed on Twitter: @safitaye1.

Alias Wardak is a lecturer and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Siegen, Germany. He can be followed on Twitter: @AliasWardak.

Afghanistan Times

Afghanistan Times