As peace talks in Afghanistan unfold, the Taliban’s positions on a number of critical topics to be discussed with the Afghan government remain ambiguous or undefined. The group has undertaken some preparatory deliberations but has a long way to go before it reaches consensus on ideas for Afghanistan’s future. It is vital for the talks’ eventual success that the insurgency determine a coherent political vision, accept an open debate in Afghan society of its positions and demonstrate a willingness to compromise at the negotiating table. The group’s vision should include clear positions on what it wants to change as compared with the post-2004 Afghan constitution and political system, and by what mechanism; how to protect the rights of women and minorities; and how to restructure Afghan security forces, including what role, if any, Taliban fighters should have therein. The U.S., other donors and Afghan civil society actors should engage with the Taliban, to the extent possible, to nudge the movement in this direction.

The urgent need to firm up negotiating positions and prepare constituencies to accept compromises exists on both sides.

The urgent need to firm up negotiating positions and prepare constituencies to accept compromises exists on both sides. Kabul has been relatively transparent regarding its vision and can be expected to seek to preserve the status quo as much as possible. The Taliban’s political views are more opaque, however, and predicting where they may and may not be amenable to compromise requires a greater degree of interpretation from a more limited set of data. Accordingly, this report focuses on elucidating Taliban perspectives, evaluating to what extent the last year’s developments reflect ideological shifts, and identifying what questions the group needs to answer in order to genuinely engage in negotiating peace.

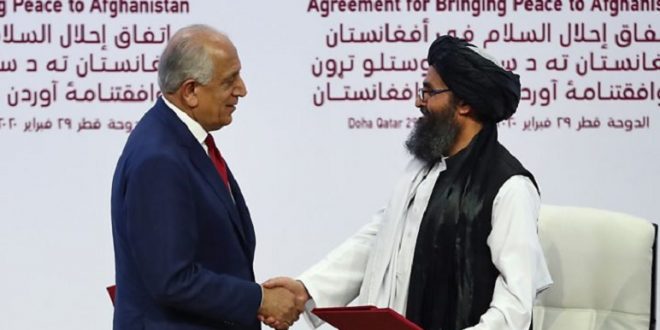

The Taliban have historically avoided the internal debate and risk to cohesion that would come with forging consensus on difficult questions of governance and ideology. The group’s core ideals are broad and define its objectives: ridding the country of foreign military forces and re-establishing what it considers legitimate, Islamic rule. The Taliban believe themselves close to reaching those goals, having survived as an insurgency and expanded far beyond their geographical and tribal roots since the U.S. and allies toppled their regime in 2001. After more than a year of bilateral negotiations, on 29 February 2020 the group signed an agreement with the U.S. that secured a phased foreign troop withdrawal in exchange for anti-terrorism commitments and a pledge to negotiate with the Afghan government, something it long refused to do.

In the months following the 29 February agreement, the Taliban and the Afghan government have stonewalled each other, resisting swift compromises on a prisoner exchange and a reduction of violence to levels more conducive to peace talks. The atmosphere for intra-Afghan negotiations is tense and, with the U.S. seemingly determined to downgrade its involvement in Afghanistan, an already fragile process is fraught with high stakes. Many in the Afghan government and civil society worry that talks may presage the unravelling of legal, social and economic achievements made since 2001. Widespread uncertainty as to the Taliban’s aims deepens these fears.

The Taliban’s ambiguity on their ambitions for a post-peace settlement exacerbate such fears. The group has done little to demonstrate its preparedness for meaningful compromise, perhaps precisely to maintain cohesion and reinforce its bargaining position. Its political wing promises global audiences that a future Afghan state in which the Taliban play a leading role will be a responsible member of the international system. Yet, internally, the group has left many questions unanswered or permitted maximalist positions to flourish. Since 2018, representatives have assured diplomats that they seek an “inclusive” government in Afghanistan, but some members still claim to be fighting for a restoration of the Emirate the group established and ran exclusively in the 1990s. The group’s external statements on women’s and minorities’ rights are vague; its internal stances vary greatly, guided less by a universal policy than by local customs and individual commanders’ beliefs. It is even unclear what it hopes for its own fighters’ futures – that is, whether they should be incorporated into new Afghan security forces or gainfully employed elsewhere.

Many conflict actors enter negotiations with maximalist positions and adjust their stances as talks progress, sometimes over the course of years, but the Taliban are a hardened military organisation with a history of intransigence. To bolster prospects for constructive negotiations, the group should continue to shift its strategic communications away from war-related messaging and open itself to wider engagement with Afghan civil society, humanitarian agencies and other stakeholders. For talks eventually to succeed, the Taliban will need to accept – and convince the majority of their armed members of – the need for compromise to truly settle decades of brutal conflict.

Afghan civil society actors and foreign donors should encourage broader engagement. The Afghan government should mirror any shifts that occur in the Taliban’s behaviour and rhetoric, acknowledging and reciprocating any spirit of compromise. Foreign governments supporting the peace process should encourage the Taliban to undergird their participation in negotiations with substantive internal debate and expanded external dialogue. While the Taliban urgently need to begin establishing consensus on internally contentious questions, the agenda and pace of negotiations should be structured in a way that allows them time to do so on key issues.

(Crisis Group)

Afghanistan Times

Afghanistan Times