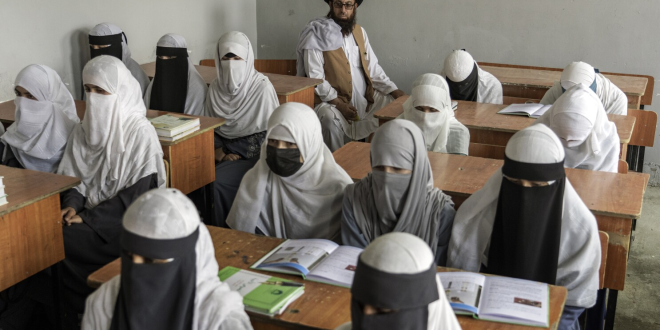

KABUL – When the Taliban fell from power in 2001, women in Afghanistan were allowed to return to school after being banned from education since 1996. A new study, co-authored by education expert Raja Bentaouet Kattan, economist Rafiuddin Najam, and myself, analyzes the significant economic benefits that followed the reopening of educational opportunities for women.

Using data from Afghanistan’s Labor Force and Household Surveys conducted in 2007, 2014, and 2020, we found that expanding education for women dramatically improved the nation’s economy. The infant mortality rate halved, and the gross national income per capita nearly tripled, from $810 in 2001 to $2,590 in 2020.

A major driver of this economic growth was women’s increased participation in the workforce. While the return on investment in education was low for the general population, it was notably higher for women. For every additional year of schooling a woman received, her earnings increased by 13%, surpassing the global average of 9%.

However, Afghanistan’s progress took a major setback when the Taliban resumed power in 2021, once again banning girls and women from education after the sixth grade. This has severe economic consequences. Our research estimates that the total economic loss from excluding women from education could exceed $1 billion annually. This represents a potential 2% decrease in national income, and does not include the broader social costs of limited educational opportunities for women.

Our study highlights the high economic cost of denying women access to education and work. By comparing the years from 2004, when education expanded to include both boys and girls up to the ninth grade, to 2020, we discovered that excluding women from the workforce could result in an annual loss of over $1.4 billion, further exacerbating poverty and inequality.

Investing in women’s education brings not only individual benefits but also positive social and economic outcomes that can endure for generations. Beyond financial returns, educated women improve school attendance and health outcomes for their children. Our study suggests that the cost of the education ban goes far beyond economic numbers and deepens intergenerational poverty.

Future research could explore not only the economic benefits of women’s education but the wider social advantages. Studies could measure the ripple effects of breaking cycles of poverty, improving public health, and reducing inequality.

Every day the education ban persists in Afghanistan, generations of women and children fall further behind. The compounded losses are robbing the nation of its potential and leaving the dreams of countless women and children out of reach.

Afghanistan Times

Afghanistan Times