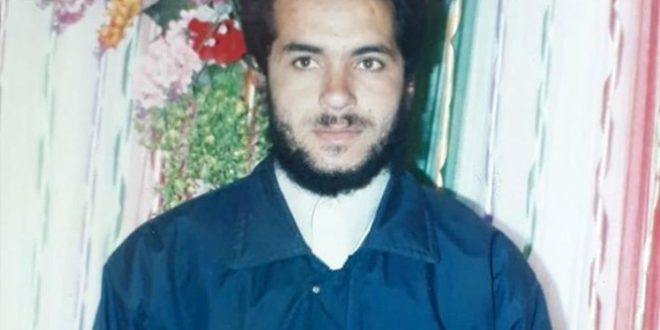

By Guantánamo ISN 3148 (aka Asadullah Haroon)

The Guantánamo military base is almost invisible to the world; the detainees held here have totally vanished from the world. We are nameless, faceless, referenced by an internment “serial number” – as if we are pieces of hardware, no longer human. A name makes a person individual and unique. Serial numbers are for inanimate objects. I am No. 3148. It is easy to mistreat something called No. 3148. A number does not have dignity.

Importantly, then, I am also Asadullah Haroon, the Afghan citizen from Nangarhar. My wife waits year after year for news that her husband is coming home. My infant baby, Mariam, is now a teenager.

Twenty-three of us “nobody numbers” remain here in Guantánamo. None is Afghan but me, so there is nobody who speaks either Pashto or Dari and I am in danger of losing my language. At least No. 1094, No. 1460 and No. 1461 are Pakistani, and we can speak some Urdu. No. 1460 was so badly tortured, though, that he would rather live in another block essentially alone with his sad thoughts.

Closing out the “no value detainees” (the NVDs) we have No. 27, No. 28, No. 38, No. 63, No. 242, No. 244, No. 309, No. 569, No. 682, No. 685, No. 694, No. 708, No. 841, No. 893, No. 1016, No. 1017, No. 1453, No. 1457, and No. 1463. …

At its peak, there were some 760 no value detainees at Guantánamo—the largest group were Afghan, some 219 of us NVDs. Thus far, 218 Afghan NVDs have been released, and just one remains – me.

Some will think that because I am still here after 13 years, I must be guilty of some crime – even though I have been held without charges or a trial. But then prejudiced people thought that everyone here was a “terrorist”. We are prisoners of a war that has long since ended. And even those who take sides in a war, one in which their country is invaded and the invader kills children with drones, have done nothing wrong. The only way to commit crimes in a war is to do what the U.S. has done, and deliberately kill civilians and torture prisoners of war like me. As the faceless and numbered men told their stories, the world began to understand what terrible mistakes had been made in sweeping up so many people and bringing them half way around the world to this Cuban prison. There was No. 1154, Dr. Ali Shah Mousovi, a paediatrician from Gardez, who fled the Taliban and worked for the United Nations. His wife, an economist, and three small children, waited for years before he was released without charge.

There was No. 1009, Haji Nusrat Khan, an 80-year-old from Sarobi, who was brought to Guantánamo on a stretcher. A stroke had left him paralyzed and bedridden. “Look at my white beard. The Americans took me from my home and country with a white beard,” he said. “I have done nothing at all. I have not said a word against the Americans.” He—like, all the rest, was never charged. His old age didn’t safeguard him from “countless humiliations”: he was beaten, injured, stripped naked in front of female soldiers. On one occasion, soldiers tied him tightly to a wooden board and left him lying on the ground for some time. One of the soldiers finally glanced down and asked how he was doing. When the interpreter translated. Nusrat began to laugh. “You must be an idiot to ask me this,” he said. “I am a paralyzed old man, and you have tied me like a dog on the floor. Look at me. How do you think I am doing?” Soon after his release, Nusrat died in his Sarobi home.

There was No. 1001, Hafizullah Shabaz Khail, a University-educated pharmacist and a staunch supporter of Hamid Karzai’s ascendancy. There was No. 1021, Chaman Gul, who worried incessantly about his aging mother. And No. 560, Afghan Wali Mohammad, who used humour to mask his pain. There was No. 1002, Afghan school teacher Abdul Matin, accused of owning a Casio watch. The list goes on. After years of mistreatment, mental anguish and incalculable indignities—218 of 219 have been released because they were no threat to anyone, although no doubt some suffer profound depression after their experience.

That means the U.S. has released 99.5% of the Afghan NVD’s. That leaves only me. I am No. 3148, Asad Haroon, and I have watched the others go home. I try to keep busy so I don’t go mad. Sometimes I wonder whether my government has totally forgotten me—I have never been visited by an Afghan delegation. I worry that my countrymen do not care about me. I am nobody—I admit it. I was taken from my home country of Afghanistan all those years ago, flown to this dreadful place, and forgotten. I see the others being released and, while I am happy for them and for their families, it deepens my gloom.

As prisoners are released every day as part of the peace agreement, or to let them go home to help their families during the crisis of this virus, I ask myself the same question every day: Will I ever see my wife and daughter again? Will my respected father and my dear mother still be alive even if I do come home?

Afghanistan Times

Afghanistan Times